Date: Sunday, May 14, 1995

Start Location: Humboldt County Fairgrounds, Ferndale

Number of Starters: 2,500 plus

Tour Director: Larry Tubbs

Top Finishers

1. Mike Pigg, 4:58:32

2. Jim Allen, 5:03:11

3. Damon Kluck, 5:04:59

4. Gary McNerney, 5:11:44

5. Brian Fennerty, 5:14:46

6. Bob Beede, 5:18:54

7. Brad Taylor, 5:25:54

8. Andrew Shaffer, 5:34:27

9. Larry Trager, 5:37:18

10. Vince Smith, 5:55:20

1. Lisa Claasen Meinze, 6:24:34

2. Linda Roush, 6:35:47

200 Mile Finishers

1. Kevin Hodge, 12:04:52

2. David Berstein, 12:16:05

3. David Andersen, 12:26:58

4. Lawrence Kluck, 13:20:26

5. Dick Koenig, 14:45:28

6. Christopher Lavertu, 15:34:51

Times-Standard article, “Deadline nears for TUC ride”, by Dave Gallagher, May 11, 1995, Page B3. Click on the article for a larger view.

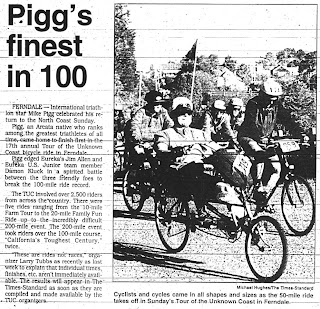

Times-Standard article, “Pigg’s finest in 100” Michael Hughes photo, May 15, 1995, page B1. Click on the article for the larger view.

Times-Standard article, "Results- Cycling Tour of the Unknown Coast," May 22, 1995, Page A8. Click on the article for a larger view.

North Coast Journal Cover Story, April 1995, by Tim Martin. Click on the link below for the article from the journal. An unformatted text version of the article is listed below.

http://www.northcoastjournal.com/APR95/COVER.HTM

APRIL 1995 - COVER STORY

California's Toughest century

by Tim Martin

It is 6 on a cold, drizzly morning - which is to say a typical spring day - in the town of McKinleyville. A lone cyclist glides down the high-way, leaning over the handlebars, headed for Eureka. The 17-mile ride will be a small part of this man's daily training. He will also swim, ride 20 miles at lunch and cycle home in the evening. On weekends, he will ride another 100 miles.

Larry Tubbs, 55, is a cyclist to the bone. He's been making this daily bicycle commute five days a week for 13 years. Only the drum-banging (Still going! ... ) bunny in the battery commercials can rival Tubbs in persistence.

"When I first met Larry he didn't even own a car," said his wife, Linda.

At 6 feet, 205 pounds, Tubbs is cycling's equivalent of Orson Welles - expansive. He is known by admirers to be punctual, genial and incredibly sincere. In fact, his sincerity is such that before he finishes speaking, businessmen - a close-fisted lot by nature - are applauding and passing around the cap.

Others call Tubbs a curmudgeon, an intolerant my-way-or-no-way promoter with all the finesse of an Army tank. One fellow cyclist called him a "schmoozer" who can shift gears faster than a well-oiled deraileur.

Although Tubbs is a study in contrasts, his rough charisma and galloping hubris lay at the center of everything that's happening in local cycling. And the Tour of the Unknown Coast, scheduled for next month, is at the center of that sport.

The Tour is a ride built by Larry Tubbs. Actually, it is a series of family rides, 10, 20, and 50 miles in length (see sidebar). But the Tour is best known for its century, a 100-mile ride with a combination of challenging climbs, stiff headwinds, corkscrew descents and treacherous turns. It has been described as "California's Toughest Century."

How tough is the Tour?

"When Olympic cyclist Lance Armstrong rode the TUC, he came into the bike shop and bought a 24-tooth rear sprocket," said Dave Parker, co-owner of Arcata's LifeCycle.

"The pros usually never go to anything more than a 21-tooth."

Why do they do it? Some ride for the raw, undiluted pleasure of the activity. Others ride it to test themselves and their limits. Still others feel that the 100-mile ride brings out a primal feeling.

"The first tour was in 1967," Tubbs said. "It was ridden by a group of local cyclists headed by Ron Barager, a mechanic for Mad River Bike Shop (now Adventure's Edge). Ron was the founding father of the Tour. He had ridden in Europe and was looking for a comparable course in the United States."

From 1967 to '77 the Tour became an annual event for Barager. It was a perfect route - no traffic, good hill training, and it brought you back into Ferndale.

Lynn Smith of Arcata recalls her first Tour.

"I rode it in '76," Smith said. "It sounded fun, so I did it as a lark. There were no officials, and no start time. We left Fortuna early in the morning and made it back nine and one-half hours later.

"The fog came in part way through the ride and I couldn't see the road 10 feet ahead. That's why it took so long. I was tired after the ride, but it felt good."

"Not many people are aware that the TUC started as a fund raiser," Tubbs said.

St. Bernard Elementary School raised funds for its Parent Teacher Organization from 1977 and continued for the next 10 years.

"Since then, Tour money has been donated to organizations including the Special Olympics, Safe and Sober Graduation, the Red Cross, the Petrolia Fire Department, Humboldt Community Access and Resource Center," Tubbs said.

According to TUC records, there were as few as 150 participants in the '78 Tour. Eight years later the number had climbed to 430. By '87 the Tour attracted more than 700 riders. That year, St. Bernard's pulled out.

"St. Bernard's gave up the TUC because of liability," said the Tour historian Paul Stanley. "That's when a group of cycling enthusiasts met and decided to keep it alive. I was there at that meeting. So was Larry Tubbs. If it hadn't been for his organizational efforts and personal dedication to the sport, the TUC might very well have languished that year."

Stanley, 58, is addicted in a high-spirited way to long-distance cycling.

"I used to be an alcoholic," Stanley said. "I drank wine by the gallon. I was also overweight and had a lower back problem. A Bay Area chiropractor told me `Get on a bicycle.' He said cycling was very good for the back. I borrowed a bicycle and rode up Mount Tam."

Stanley came back with his eyes red, pupils dilated and a smile on his face, like someone who had just fallen 10,000 feet off a mountain and landed on a truck loaded with pillows. Stanley fell in love with cycling, simple as that.

As Stanley began to train, he discovered an old adage: Put your body through some hoops, and it responds. He began riding longer distances - 20, 40, 60 miles. In 1988 he decided to ride the Tour.

"When I first did it I was surprised," Stanley said. "There were lots of elevation changes, which got worse as I got into it. And the winds! Debilitating. Especially along the coast.

"Going up the Wall took everything I had. I was really suffering. After the ride I told myself, `I'm never going to do this again.'"

Fourteen consecutive TUCs later, Stanley is singing a different tune. "It's a wonderful ride," Stanley said. "If people down south knew about this, there would be even more (riders) up here.

"The scenery is beautiful. To experience it on a bike is like kissing it. To ride alongside the rivers, to feel the flow, to be among the trees. It's inspiring."

The Tour was equally inspiring to Ferndale Chamber of Commerce representative, Katherine Queen. At a meeting in Eureka, Tubbs and Queen proposed to start and finish the Tour in Ferndale. Additionally, Tubbs came up with an idea for both a race and a ride - a three-event stage race: a criterium in Eureka, a circuit race in Arcata, a time trial in Trinidad.

The TUC ride would cap off the entire affair. Tubbs was elected to direct the event. It would be called the North Coast Cooperative Classic Tour of the Unknown Coast.

"The Coors Light team came up for the race," Tubbs said. "Chico Velo (promoters of the Wildflower century) helped out. We paid them a fee to use their sanction."

The '88 Tour was a huge success. All events went smoothly, and Humboldt County cyclist Karl Moxon won the 100-miler. Impressed with the professionalism and enthusiasm that Tubbs demonstrated was the title sponsor, the Co-op.

"Larry Tubbs is superb at building drama and organizing an event," said John Corbett, Co-op general manager. "He puts on a class A race."

Spirits were high the following year. Tubbs again directed the event, and the Co-op stayed on as sponsor.

"'89 was another good year for local talent," Tubbs said. "It was the year triathlete Mike Pigg won the Tour in a record-breaking time of 4 hours, 42 minutes."

Pigg's time was impressive, Tubbs explained, because he rode the entire course alone, without the advantage of the "slingshot" drafting exchange shared by team riders.

Wind resistance is a big factor in bicycle racing. When a cyclist drafts, he positions himself behind a row of teammates to keep the air moving smoothly around him, thus conserving energy. To go the same speed as you do when riding by yourself, you use 60 percent effort. You use an additional 30 percent to 40 percent more energy when riding by yourself.

Pigg's solo effort did something else: It erased Jim Allen's long-standing course record of 4 hours, 45 minutes, an achievement many thought impossible.

Allen's commitment to personal conditioning is unmatched. When he is riding well, when the speed is up, he is almost untouchable.

At 44, Allen has spent a good portion of his life on the saddle. He has traveled across the country on his bike and won countless races (including the U.S. Cycling Federation nationals). He has completed the TUC 12 times, and has won it probably more than anyone.

"I started way too late to go professional," Allen said. "I was 30 when I started riding. Most retire at 32 or 33."

Jim's brother, Tom, 47, is an equally talented cyclist who won last year's TUC 50-mile ride in 2 hours, 24 minutes.

In preparation for the Tour, Jim rides 300 to 350 miles a week. "I used to ride 400 miles a week," Allen said. "It (cycling) takes a lot of time. Over the years you develop a base. You get smarter. Otherwise, it wears you out."

Worn out was what Tubbs began to feel in his dual role as TUC race director and full-time insurance agent.

"By then the race had built up to 1,000 participants," Tubbs said. "It was a major undertaking to stage a three-day event, and there was no compensation. My phone was ringing off the hook.

"The Tour had become the focus of my life. And no one in the Humboldt Cycling Club assisted in taking on any of the duties."

Tubbs, himself a member of a cycling club, said he requested help in organizing the Tour. But problems were brewing. John St. Marie and several other HCC board members were not happy with the direction the Tour was headed.

"Larry started HCC," St. Marie said. "He was the first president. When Larry directed the Tour, there was participation from the club, but there was alienation, too.

"HCC's stand was that the Tour was primarily for local folks. We felt that racing or timing the event took away from the family-oriented activity. And we didn't want to spend advertising dollars outside the area.

"But Larry had bigger ideas. Then, there were elections, and Larry didn't get re-elected. That's what started the friction between Larry and the cycling club."

Club politics aside, the '90 race went as planned and was notable for attracting a number of elite riders, including Greg Spencer and the Specialized Team from Seattle. Spencer set a new (team-assisted) record of 4 hours, 34 minutes. '89 champion Sandra "Pony" Klingel of Eureka returned for another victory in a time of 6 hours, 38 minutes. Shortly thereafter, Tubbs resigned as TUC director. According to John Corbett, the timing couldn't have been worse.

"The '91 race was to be a pivotal year for the Tour," Corbett said. "We were all set to go on television. The Tour de Trump was going under, and ESPN was looking at our event. The Co-op was prepared to invest over $8,000 in the race. But the constant disputes between Tubbs and the cycling club eventually made us pull the plug."

After Tubbs resigned, St. Marie stepped in to become TUC '91 director. He said he received little help from Tubbs.

"I came in pretty naive to the job," St. Marie said. "It was a rude awakening."

Against this backdrop of turmoil came a calamity: A local cyclist, Tom Ross, was struck by a car while training for the Tour.

Ross, of Fortuna, was not exactly an exemplary athlete. He smoked, chewed tobacco and ate anything with plenty of fat on it. Then his daughter was born, and all that changed.

"I threw my chewing tobacco out the window on a deer-hunting trip," Ross said. "I decided to set a good example for my new daughter. It was time to lead a better life."

In '87, Ross entered a road race at College of the Redwoods. Soon after that he began riding longer distances.

He loved the solitude, the mental release of being on a bike. This was the "something more" he had been looking for. The following year, Ross decided to enter the Tour.

Ross was a strong competitor. He challenged every inch of the Tour. By the time he reached the 80-mile mark, he was hurting. His knees shook, and his legs filled with lactic acid. Then Ross started up the Wall and something strange happened.

At the edges of old maps, cartographers would draw sea monsters with which to warn of the unknown. In disregard to the possible danger, a sailor had no idea what fate awaited. Likewise, Ross had no idea what fate awaited him as he painfully inched his way up the Wall.

Then, in one magical moment of fatigue and serenity, he encountered a strange dislocation of ordinary time. Tom Ross stepped over his pain, and found himself suspended in a state of perfect aerobic motion.

"I went into a zone and that was all," Ross said. "I didn't remember anything after than until I reached Ferndale."

Ross finished the ride in a time of 5 hours, 17 minutes. The following year he was back to prove the time was no fluke. He completed the course in 5 hours, 24 minutes.

Here was a young man going places. He was a cyclist with a head full of dreams and almost a lifetime in which to accomplish them.

Then, in March of '91, on a training ride to Ferndale, Ross was struck from behind by a drunken driver and left paralyzed from the waist down.

He prefers not to talk about the accident.

"The accident is behind me," Ross said. "I don't want it to be the central part of my life. I'm at College of the Redwoods now, studying general education and business, getting up to where I should be.

"The support I got from other people has helped me not be bitter. A lot of it is because of people like Larry Tubbs. He's played a big part in helping me get to where I'm at today."

"After the accident, Co-op contacted Larry and asked him to come back and take part in the Tour," Stanley said. "He decided to do it, if the proceeds of the ride would go to Tom Ross and his family. Co-op agreed. So Tubbs laid aside his problems with the club and pitched in as TUC '91 promotions director."

The action proved to Stanley that even Larry Tubbs' charcoal soul has a soft chewy center.

Unfortunately not enough planning had gone into the '91 event. Even with Tubbs' involvement, TUC's unlucky 13th edition would be remembered for a paltry 981 starters.

"In '91 the Tour almost collapsed from lack of organization," recalls Corbett. "HCC had to scale it back quite a bit."

The event, which was scheduled to feature four stages, was cut back to two: a criterium in Arcata and the Tour.

Arcata's Vince Smith rode the '91 Tour. Smith, 44, has been riding the TUC for 16 years, and has a personal best of 5 hours, 38 minutes.

"Last year I did 12 centuries," Smith said. "The Tour was by far the hardest. The course is unpredictable."

For Smith, the most difficult part of the ride happens to be at the start.

"That's because everyone is going faster than they should go," Smith said. "The Tour starts like a race. You can't go at your own pace. You have the psychological aspect of staying in touch with the group. If you drop out of the pack, it's over.

"Half the riders go out over their head. Another big mistake people make is that they don't eat right away and run out of energy. It's important to start eating as soon as you leave Ferndale. And don't stop."

What happens when a rider goes out hard or doesn't eat properly? They bonk, a cyclist term for fatiguing, or hitting the wall. When a rider bonks, he is left struggling against the course like a mastodon in a tar pit.

"Riders also bonk if they haven't trained properly for an event," added Smith. "A good formula for the Tour is, six weeks before the race ride a full century. Three weeks later do a second one. And three weeks later, do the race. And don't train at an anaerobic level too much. It wears your body out."

For both the cycling club and Co-op, the '92 event would again be a trying experience. TUC '92 was besieged by organizational problems, financial difficulties - and then came a major earthquake that caused widespread damage to much of the Lost Coast area and the town of Ferndale. Because of the quake, the Tour was rescheduled to a month later.

That year the squabbling between Tubbs and the Humboldt Cycling Club continued and Tubbs did not participate. The event was eventually managed by the HCC.

"When (Tubbs) pulled out, HCC formed a tour committee because we wanted it to continue," said Carol Schillinger, a member of HCC.

Among the many cyclists happy to participate in TUC '92 was Tom Ross. He came back on a specially equipped bike to ride the 50-mile event tandem with Ross Jantz, an HCAR employee.

In an emotional and stirring moment, Ross pulled off the course just short of the official finish. He had not ridden the 50 miles for applause or adulation. Nor had he done it for sympathy. Tom Ross rode the Tour for the same reason he had always ridden it: to challenge himself.

"It was a good feeling doing it," said Ross, "but it wasn't the same. It was an aided 50 miles. It wasn't truly me."

Another cyclist eager to ride in TUC '92 was Eureka's Larry Kluke. At 46, Kluke is hardly a candidate for Geritol. A husband, father, role model, attorney and a fearsome mega-mile cyclist, Kluke has ridden in 33 organized centuries, and completed several 200-mile rides, including Death Valley.

"I never get bored," Kluke said. "It's interesting. I get into a state where I monitor my body and don't go over the edge. You run out of glycogen, and it's terribly difficult to catch back up."

Kluke will need all the glycogen he can muster when he competes later this year in the Paris-Brest-Paris race.

The event, scheduled for Aug. 21, a cycling race from Paris, France, to the coastal city of Brest and back, has become the Olympics of club tours. The 768-mile trip is held every four years.

"The Paris-Brest-Paris Race is a 100-year-old race," Kluke said. "All participants must finish in under 90 hours. Last year's race had 4,000 riders. I figure I can finish it in 60 hours, with a rest."

To ride the Paris-Brest-Paris, Kluck will need to ride four qualifiers, or brevets, of 200, 300, 400 and 600 kilometers (620 miles). For a cyclist who has ridden the TUC more times than he can recall, the brevets should pose little problem.

Like Kluke, Tubbs couldn't stay away from the Tour. While he stepped back in '92, Tubbs came back with renewed spirit the following year.

Tubbs claims he was appointed TUC '93 director by the Co-op, which owned the rights to the title of the event. The Co-op's Corbett said not exactly.

"In '93 the Northcoast Cooperative sold to the HCC any legal rights it may have to the Tour," Corbett said. "This was done because at the time the Co-op purchased the Tour, we promised the club that it would sell the race back to them if we should ever decide not to sponsor it."

Amid the confusion, Tubbs continued to promote the ride locally and nationally.

"I called Jay Leno's CBS office and asked him to introduce the ride on the air," Tubbs said. "Leno did it. He joked about the distance of the ride, and mentioned that it was a benefit event.

"TUC '93 was a big success, with almost 2,000 cyclists in attendance," added Tubbs. "The rider turnout was phenomenal."

On the down side, '93 will be remembered for its shortage of food and water services.

"It was a logistical nightmare," recalled Tubbs. On race morning, there were people lined up at the registration tables.

Cycling is the only sport - with the possible exception of bowling - where eating and drinking are an integral part of the action. The average rider, if you're riding hard - say about 20 mph - will burn approximately 11 calories a minute. If you're out for 60 minutes, that's 660 calories - a lot of food.

One unhappy rider that year was Bob Ornelas of Arcata. "At the base of Panther Gap and Endless Hill there was no water. It's not healthy to make people climb a hill with no water."

Ornelas is a member of Team Lamprey, which consists of the North Coast residents Dick Koenig, Peter Lehman, Brian Cox and Ornelas. They excel in riding the slipstream of other cyclists.

"We're not fast, but we're not slow," Ornelas explained. "We're sucktorial. If the other cyclists are faster, we hang on as long as we can. Team Lamprey grabs on and pretty much sucks the life out of the competition."

Ornelas loves the Tour, but he does not agree that it should grow bigger. "Tubbs fails to see his limits, and the problem of that many people on that little road," he said. "He should limit the race to 1,000 riders.

"To me, personally, Tubbs is no hero. But like most local riders, I'm grateful that someone has taken it on themselves to ensure the Tour's continuation."

You can fry a hamburger on Schillinger's forehead when you mention TUC '94. It was a year of even greater friction between Tubbs and the cycling club if that were possible.

"Last year, prior to the '94 Tour, HCC went to Co-op and told them we wanted to buy the Tour," Schillinger said.

"That, in effect, did happen. When Larry found out we had purchased the rights, he started another `tour'; he called it `Tour of the Lost Coast.'

"Larry was going to hold his tour on the same day, and on the same course. He sent out flyers and put advertisements in cycling newsletters. And he did it all with absolutely no warning."

A meeting was called and all parties showed up with attorneys. When the dust settled, the race was on, to be run by a steering committee. But Tubbs was still out in front banging the drum.

"In '94 we set a goal of 2,000 riders," Tubbs said. "We had 2,091. Jim Allen won the men's ride in 5 hours, 15 minutes. And Mary Pincini, of Arcata, won the women's ride in 6 hours, 6 minutes.

"The Tour is not only for hammer heads," said Tubbs' wife, Linda. "Last year a 67-year-old woman participated in the ride. It's a family ride, as well. Brian Claussen and his family ride it every year."

Claussen, a Luthern minister in Ferndale, has ridden the Tour 13 years straight. The family does it as a reunion.

"May 14th is my birthday, anniversary and Mother's Day," Claussen said. "We celebrate it all. My older brother, Steve, rode it the first year. Then all five brothers, dad and my sister-in-law joined in. My younger sister, Lisa Meinzeu has won twice in the last couple of years."

Last year Brian Claussen and nephew Joshua Hoopes, 14, set a tandem record. Their time was 6 hours, 7 seconds.

What lies ahead for next month's TUC?

Already, Tubbs and the new TUC committee are scrambling to produce a spectacle even more entertaining than ever. For '95 he has added a 200 mile ride to the Tour - a ride called "Toughest Times Two."

"This will be our first year for a sanctioned 200-mile ride," Tubbs said. "Seven people have already registered."

And there will be enough food to save an African nation, Tubbs promises.

While the Co-op has not renewed its option to sponsor the Tour, interest remains.

"I was always amazed," Corbett said. "Despite all the human foibles behind the scenes, come race day it all came together."

"This year the Tour will be celebrating its 17th anniversary," Tubbs said. "Yakima has come on board as a key sponsor. The ride is expected to expand to a maximum of 2,500 participants, the biggest field ever."

A tour of the tour

The Tour starts in Ferndale. In the chill darkness before dawn, riders unload bikes from car carriers and cruise the streets. Others make last-minute preparations. Jackets are pulled on. Helmets and gloves appear. The excitement is almost palpable.

Snap! At the signal to start, you attach your feet to the clipless pedals and accelerate out of town with the pack.

The first section of the course is relatively flat. Hands on the drops, you wind your way south along the Eel River, hammer through the Avenue of the Giants and fly past Pepperwood.

The first major climb begins at Albee Creek and continues up the 2,700-foot Panther Gap ridge. Conversation wanes, water bottles appear. The pack begins to fracture.

From Honeydew (the 50-mile point on the course) to the Mattole Valley, the silence is broken only by heavy breathing and the constant whir of thin tires against pavement. After Mattole, you wind your way down to the Lost Coast, a wide stretch of beach where breakers pound against the rugged shore, and strong winds threaten to blow you to a standstill.

Geographically, this is lowest point on the course. Psychologically, the ride gets a whole lot lower than this. Looming a few miles ahead is the Wall, a grueling 17 percent grade, a one-mile ascent that leaves even the best cyclists fumbling for their shifter and praying to the Quad God for strength. No one smiles on the Wall. No one talks, or looks up from the pavement.

There are several ways to climb the Wall: You can grab a low gear, stand on the pedals and push your gears (and body) to exhaustion. You can embark on an irresolute, crooked stitching back and forth across the road until you find the top.

Or, you can walk - one hand on the bar, one behind the saddle, body folded at the waist, head bent downward. It doesn't matter how you climb the wall. The enabling motto is: Get to the top by whatever means possible.

Once you've made it up the Wall, prepare for the next challenge: the Endless Hills. The Endless Hills, 17 miles of intense climbing, leave your lungs torched.

You'll spend a lot of time in your geriatric gears on the Endless Hills. Everyone does. Try to relax. You'll need every drop of adrenaline you've got to make it to the Wildcat. Finally you crest the last hill. Now comes the descent. Nestle into the drops and dive in.

The ride down Wildcat is an exhilarating, white-knuckled swoop; a semi-breathless, 40-mph tumble on sharp (and sometimes graveled) switchbacks that leaves your mind in a cocoon of concentration, empty of everything but fear.

Careful. Fall, and - in the colorful language of cyclespeak - you will "crayon" (leave a long, red streak on the asphalt). Stay aboard, though, and you will jam back into Ferndale, and across the finish line.

For families, too

The 1995 Tour of the Unknown Coast will be held on Sunday, May 14. The 10-Mile Farm Tour is a safe, scenic ride through the Ferndale farmlands. Excellent for one-speed bikes.

The 20-Mile Family Fun Ride follows along the Blue Slide Road and returns along the same route to Ferndale. The ride has several hills.

The 50-Mile Challenge travels down Blue Slide Road, to Highway 101 and the Avenue of the Giants, and back. The Challenge also contains several hills.

The Century (100 miles) travels south from Ferndale to the Avenue of the Giants, up Panther Gap, down into the Mattole Valley, up the Wall, and Endless Hills, down Wildcat, and back into Ferndale.

The Toughest Times Two (200 miles) follows the same course as the Century. All rides are mass-group starts: 200 mile, 5 a.m.; 100 mile, 7 a.m.; 50 mile; 8 a.m.; 20 mile, 10 a.m.; 10 mile, 11:30 a.m.

All rides start and finish at the Humboldt County Fairgrounds in Ferndale. Register by calling TUC Director Larry Tubbs at 839-8296.

Tim Martin is a part-time writer and a full-time heating and ventilation specialist at Humboldt State University.

Comments on this story? E-mail the Journal:

1 comment:

This was my first time riding the TUC. I just wanted to see if I could even complete such a ride. I used my mountain bike with slicks. A friend that was riding with me crashed near the top on the descent to Honeydew because he waved at some friends along side the road. He broke his forearm pretty bad, and still has the metal plate in it to this day. I remember the beach section that day very well: it was sunny, warm, and no wind whatsoever. The rest of the course had pretty much the same conditions, once the morning cool faded. The ocean was oil-slick smooth, even by the time I arrived there, which must have been well after 1 p.m. Six-mile was very fast that day. I think I finished in around 9 hours.

Post a Comment